What M.I.A. Really Wants To Say With Her Surveillance-Combating Brand OHMNI

“I could be a genius, I could be a cheat.”

Those who have followed M.I.A.’s career will know she’s made a name for being staunchly anti-establishment. From team ups with Julian Assange, the founder of Wikileaks, to battles surrounding censorship of her music videos, the London-based musician is the antithesis of conformity, a vocal advocate of free-speech and an opponent of the clandestine forces which seek to eliminate it.

The “Paper Planes” songstress is the first person of Asian descent to be nominated for an Oscar and Grammy award in the same year. Her six studio albums investigate information politics in the digital age with the 2013 track “The Message” infamously stating: “Connected to Google, connected to the government.” In the 11 years since, as the world of technology, censorship, surveillance capitalism and human-machine hybrids have vastly transformed, M.I.A. has never faltered in her pursuit of autonomy and amplifying the “Third World Democracy.”

Now, the artist is ready to extrapolate her message onto a new canvas: OHMNI.

The brand, released in June of this year, is the artist’s solution to eliminate what she deems to be the intrusive technological tapestry in our everyday lives. The clothing is made with copper and nickel Faraday fabric which is intended to deflect electromagnetic waves. The collection, consisting of shirts, jackets, hats, bags and boxers, claims to provide coverage against 5G, wi-fi and bluetooth. While 5G’s negative effects on the body have been debunked by the World Health Organization and medical researchers, privacy against big-brother tech is also top of mind. She tells us that the collection allows the wearer to become invisible against imaging drones, surveillance and data tracking.

As we sit down to talk, we take unexpected turns veering close to the edge of reality. In this liminal space, oscillating between fact and fantasy, politics and power and conspiracy and consumption, our conversation begins…

You’ve frequently referenced the political nature of technology in your music. What initially piqued your interest in this technological layer we have in our lives?

I came up during the golden age of the internet. At the time, the internet was about building communities that were driven by people discovering each other in a whole new way. Being on the cusp of that, and people discovering my music on sites like Limewire and Napster, I felt part of the evolution. Those years also gave birth to a lot of companies that we are shaped by today, whether that’s Facebook or YouTube. I experienced all of the beauty of the internet so, I cared when it started to change.

Do you remember when you first felt the power dynamics in digital culture starting to change?

When it went super corporate. That happened in 2010 when I wrote the Maya album. It was laid out to every artist, you have to monetize, capitalize, catch all your fans in a big net, collect all of their data and give it to your record label. I didn’t want to do that my fans. If I was talking about internet privacy or whistleblowers and my fans were really into that, then I could potentially be the person that they were targeted through.

It was ideological warfare. It was about influencing people’s perception. I didn’t realize that becoming a musician and being opinionated about things would be so controversial. I preferred to have the battle on my own rather than drag my fans into it.

When and how did the OHMNI platform come to be?

We launched in 2017 with a collection to complement the AIM record in collaboration with Astrid Andersen. Initially, OHMNI was supposed to be an umbrella to build a community. We tried a few different collaborations but each time it wasn’t right. So, I locked in independently, put my life on hold and things fell into place.

[Around the same time,] I wasn’t getting my visa to see my son. I didn’t want to just sit there and have a meltdown. I wanted to do something productive. My son was turning 15 and it just made sense to build a brand, teach him about technology and make something that is important for him and future generations. On his birthday on February 11, we built the brand. We started from scratch, from designing to fabric samples to sourcing factories. We launched it all within 90 days. Then, I got my visa and I was able to go to America and say “Ta-da!”

Does OHMNI mirror your creative vision in making music or is it something entirely new?

I think it’s totally new. I could have always had a brand but I never did because I didn’t want to add to the noise. I had to make a decision to make something that was personal. It was definitely ignited by the situation I was having with my son but it’s also personal because it was all done by me on a very small scale.

What does OHMNI bring to the fashion industry that we haven’t seen before?

Technological advancements aren’t going to slow down. It’s totally okay for a brand to coexist along that development. It’s not like you’re saying, “Technology is terrible, you must stop it.” You’re saying while that development is happening there can be a parallel existence of a brand that acknowledges it.

If you look at the history of clothes, nothing has really changed. Now, we have satellites, drones, nanocomputers and we still make clothes like we did in the Victorian era. Initially, the OHMNI brand I wanted to build was like that with organic fabrics but then the sort of M.I.A. thing kicked in, and it was like, “Put the organic cotton to the side for now, and just go with the technology thing, because it’s just so much more interesting.” We’re not going towards pineapples and avocado skin leather, we’re building modern day armor.

The OHMNI site contains research links with everything from emotion-detecting AI to conspiracy claims. So, tell us about the research process… what was your initial point of inspiration?

There were a few ways this [radiation/5G EMF-proof] fabric was introduced to me, starting with when I was doing the WikiLeaks mixtape with Julian Assange. I had a friend called Adam Harvey, who did a collection called “Stealth Ware.” but at that time, the fabric was super expensive, wasn’t accessible and it was a military product. It all started to come together in mind when I learned that Georg Ohm was the inventor who discovered that electrical current has a resistance. That’s why resistance is measured in ohms. Through its use in military uniforms, this material has always been used in times of resistance. So, Ohm… ohms resistance… OHMNI.

Also, from 2021 to 2024, I was wearing exactly the same pair of clothes. I lived out of one suitcase and did a whole process of cleaning out everything. It was a spiritual exercise about giving up your attachments to the material world. I starved myself of fashion. My fans would be like, “Girl, where’s your serve?” and there was just no serving happening. After I’d gone through that, I was like a blank canvas and understood the importance of functional, essentials-first dressing.

Talk to us about the anti-surveillance elements of the brand. Why were these features important to include?

If the Maya album had a sound and a look, this is what it would be. It’s an extension of topics I’ve been interested in. I’m doing this interview in London, where we are the number one surveillance city in the world. The tech companies have made enough money now with people’s data. It’s okay to prolong the access. It’s okay to have a choice of when you want to share something. I found that really freeing.

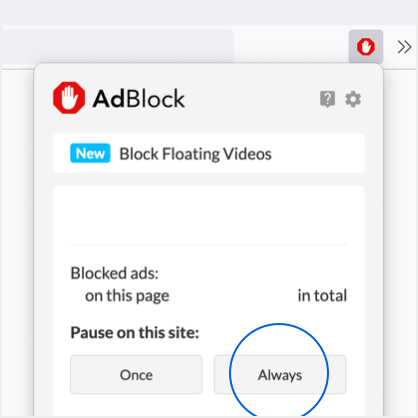

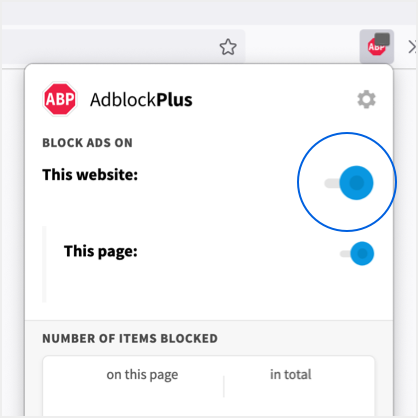

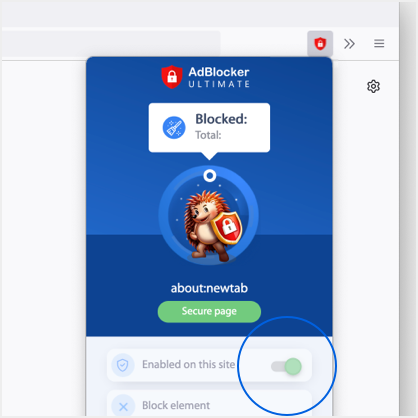

With the collection, you have a choice. We have pockets that can take you completely off grid and pockets where you can still get texts and calls. So, you’re still accessible. We just reduced the amount of zapping that it’s doing. For the puffer jacket, you can wear it just as a jacket but at the same time, you can be sat next to your internet router and feel safe. With the surveillance aspect, you can put these trousers on and use them as trousers. But, at night, you can take them off, wrap your phone in them, and no one’s analyzing your snores. It’s just like “No, sorry Tim Cook… not tonight!”

You’ve said of this collection, “I could be a genius. I could be a cheat.” What do you mean by that statement?

A lot of people’s initial thing is, “Oh, my God the tinfoil hat. She’s a conspiracy theorist!” [Meanwhile,] people have come out and said humans are hackable and [there's interest] in surveillance inside the body. That was said on a global platform at WEF four years ago. If you go to the U.K.’s government website they say that the next level of existence is augmented humans. Nobody’s calling the British government up saying, “You f-cking conspiracy theorists,” are they? No, we completely accept that as, “Wow, that is awesome. We’re going to be living in Blade Runner times.” And then you design a hat and you say, “Oh, it’s just going to stop a couple of satellites from peering straight into your skull,” and then people say, “she’s a conspiracy theorist.” That’s what I mean by “You could be a genius, you could be a cheat.” Go and listen to WEF conferences and hear what they say about harvesting data from inside your body. Then, look at my hat and then figure it out yourself.

This is the thing about the future, they try to put us in boxes. You’re either a transhumanist who believes in the end of humanity or you’re pro-humanity and you believe that humans are special as they are. That’s where OHMNI comes in. Our collection is designed to protect the human as is. If you want to be a cyborg, you can still wear OHMNI you just won’t be 100% efficient. You will be glitching a bit, definitely.

So, have you built OHMNI to achieve what you think regulations aren’t?

Regulations not keeping up with the pace of [these innovations] is a deliberate choice. Social media apps are designed like casinos. They’re supposed to be addictive. So, now, we are addicted to having attention. When people don’t get surveilled or perceived or spied on, they are starting to have anxiety issues. That’s how society built it. It’s almost like saying, “No, you need people looking at you, we want to know what you’re doing.” Everything is tech and everyone is marketable. You need downtime alone to ponder on life. We don’t have that anymore.

Do you have positive hope for the evolution of technology?

There’s always a villain who’s ready to take an idea and make tons of money. That is determined by the nature of human development as a whole collective consciousness. If you lead technology with a group of people who are extremely paranoid, biased, ignorant, racist or insecure, then technology in their hands is super dangerous. But that’s like anything, if you put money in the hands of these people it is super dangerous. If you put medicine in the hands of these people it is super dangerous. If you put humanity in the hands of these people it’s super dangerous. Technology in the hands of these people can go astray. I want to be protected against that.

In your hands, what does the future of fashion tech look like?

OHMNI sets a new precedent for what fashion can do in a commercial space. Coming from Central Saint Martins, I see a lot of the students embracing technology and working with AI. Some of the things that the students are doing are exciting in terms of design and 3D printing. Some people want to become robots and cyborgs or make dresses out of broccoli, which is very playful and I think it’s cool but, [the industry] needs to keep the conversation practical.

I think it’s important to expand the conversation of technologic use in fashion. OHMNI is anti-information stealing. It embraces the notion of technology asking how [these tools] can coexist. We are being pushed to have much more of a technological existence and living in a less surveilled area like the countryside is not a lot of people’s reality. I certainly haven’t been able to achieve this “frolicking in the fields” dream with horses, yet. So, if you’re living in the city, you need an armor. We need protection. OHNMI is engaged in finding solutions around that.